Androscoggin River Inspires Clean Water Act

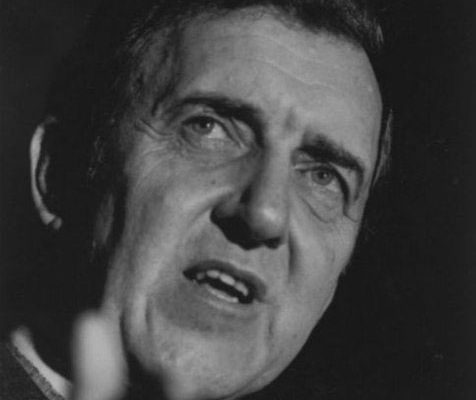

US Senator Edmund Muskie

The Androscoggin River was once so polluted that it would lose all of the oxygen in its waters. Fish became unable to breathe and died by the millions. Sometimes industrial facilities discharged dyes with their wastewater that turned the water different colors.

As many people know, the Androscoggin became so polluted that it inspired U.S. Senator Edmund Muskie, who grew up near the river in Rumford, to draft and provide the necessary leadership to secure passage of the Clean Water Act of 1972. Less well known is the fact that state-based conservation groups like the Natural Resources Council of Maine (NRCM) helped create vital early support and momentum for national action to address the sorry state of our polluted waterways.

In 2022, we celebrated the 50th anniversary of the Clean Water Act (CWA). During the CWA's 50th anniversary year, the Maine Legislature passed a bill to upgrade more than 800 miles of Maine's waterways, including sections of the Androscoggin, to improve water quality. Read NRCM's testimony on this bill.

Androscoggin River Pollution

Unfortunately, parts of the Androscoggin still do not meet Clean Water Act standards. The largest sources of Androscoggin River pollution were the pulp and paper mills in Rumford and Jay. The Androscoggin Mill in Jay closed permanently in 2023. Neither of these mills was as clean as good mills in Europe and South America, mills that are also far more efficient and likely to provide jobs over the long term.

Androscoggin paper mill in Jay, Maine, by Beth Comeau

Our Work to Clean Up the Androscoggin River

Much of NRCM’s work to clean up the Androscoggin focused on the paper mill in Jay because it was the bigger polluter of the two mills. We worked for many years to get this mill to adopt modern pulping and bleaching technologies that reduce pollution, save energy, and lower operating costs. In 2005, NRCM sued International Paper (the owner of the mill at that time). That same year, we appealed a waste discharge license for the Jay mill to the Board of Environmental Protection.

We also reached out to one of the Jay mill’s largest customers, National Geographic, over the course of several years. In the end, National Geographic did ask the Jay mill to make significant pollution reductions due to our advocacy, although not to the extent that we had hoped. Nevertheless, our work led to the biggest decrease in pollution discharges from the mill since reductions that resulted from the Clean Water Act.

Paddling on the Androscoggin River. Photo by A.Wells/NRCM

The Androscoggin runs through the heart of Maine. Its waters in Gilead support a world-class trout fishery that attracts tourists to Bethel and nearby towns. Here, the river is a source of recreation-based jobs, activities, and pride for the people who live in the region.

Further downstream, the river is much cleaner than it used to be, and people can now use it for recreation. But the Androscoggin River is still the dirtiest of Maine’s major rivers.

Banner photo: Paddling on the Androscoggin River near Bethel, by A.Wells/NRCM